7-25-2024 (issue No. 151)

This week:

Land of Linkin’ — Where I tell readers where to go

Squaring up the news — Where Charlie Meyerson tells readers where to go

Mary Schmich — Eight words reacting to the latest political news

Quotables — A collection of compelling, sometimes appalling passages I’ve encountered lately

Quips — The winning visual joke and this week’s contest finalists

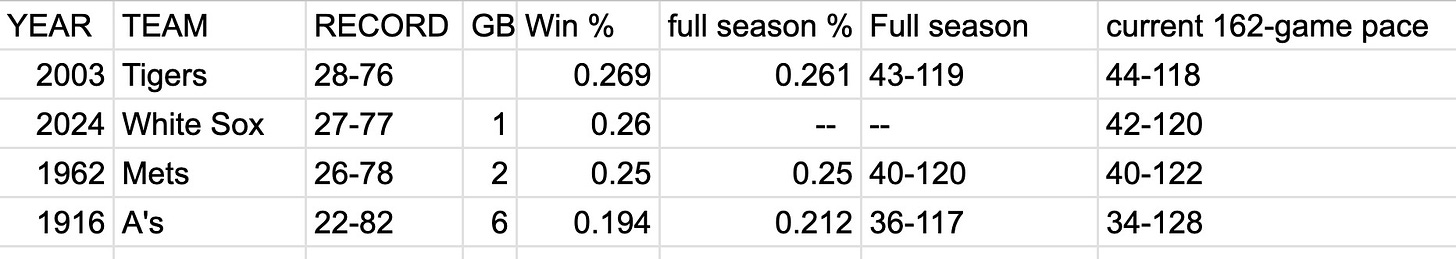

Good Sports — The White Sox are on pace to lose 120 games this season

Eric Zorn is a former opinion columnist for the Chicago Tribune. Find a longer bio and contact information here. This issue exceeds in size the maximum length for a standard email. To read the entire issue in your browser, click on the headline link above. Paid subscribers receive each Picayune Plus in their email inbox each Tuesday, are part of our civil and productive commenting community and enjoy the sublime satisfaction of supporting this enterprise.

Midsummer break

I’ll be in vacation mode the next three weeks so posting will be lighter than usual.

Last week’s winning quip

When you’re dressed all in black and someone asks, “Whose funeral is it?” looking around and saying, “I haven’t decided yet” is typically a good response. — @woofknight

Here are this week’s nominees and the winner of the Tuesday visual-jokes poll. Here is the direct link to the new poll.

ShotSpotter under the microscope

I was recently a guest on an episode on Mike Pesca’s daily interview podcast “The Gist” in which I helped the New York-based host interview an official with ShotSpotter. Here is a lightly edited transcript of that segment:

Host Mike Pesca: ShotSpotter is a service in many U.S. cities that triangulates the sound of gunfire to alert police of exactly that phenomenon. It is tremendously popular. Many municipalities rely on it, but lately there has been criticism of ShotSpotter. It does have a false positive rate that the company says is relatively small. Some cities have found that ShotSpotter alerts lead to few arrests. The cost of ShotSpotter is not cheap, though the company says it's worth it when compared to hiring and paying the benefits for police officers who don't have the ability to spot shots like this technology does.

But lately, the city of Chicago, one of the most murderous cities in the United States and one that will be on the world stage at the end of August with the Democratic National Convention, criticized ShotSpotter. Or at least their mayor, Brandon Johnson, did, calling it unreliable and overly susceptible to human error. However, he also added, they’re going to keep it running through the convention, which I can't quite understand.

So helping me understand the Chicago angle and how the technology works, how well it works, literally how it works, are two guests. One is Tom Chittum, senior vice president for forensic services for SoundThinking Inc., the parent company of ShotSpotter. The other is Eric Zorn, former Chicago Tribune columnist, who is a panelist on the excellent “Mincing Rascals” podcast and the producer of The Picayune Sentinel Substack newsletter, of which I am a charter subscriber. Tom, let’s start by having you explain to the layman how this technology works.

Tom Chittum: Well, if you had asked me before I came to work for this company, I would have assumed that ShotSpotter was powered by magic. Because how can it possibly do what it claims to do? But I know now that it is not magic at all. It's basic math, science and technology harnessed for public safety. So sound travels at a known speed in all directions. In all directions, we deploy sensors over an area. Those sensors detect loud sounds like firearms being fired. Then we calculate the time difference of arrival, how quickly the sound reaches one sensor versus another sensor versus another sensor. And then we locate where that sound came from. We use several steps after that to filter out sounds that are not likely gunfire. And then the sounds that are gunfire, we publish to our customers, the police, so that they can respond quickly and precisely to where gunfire occurs. And all that happens in less than 60 seconds.

Pesca: OK, so that sounds good, but the one thing that jumps out at me is the phrase, “eliminate sounds that aren't gunfire.” That's possible, but I'm sure it's not always perfect. Give me a sense of how you do that, how accurate it is, and maybe if you could relay a couple relevant statistics, including what is the false positive rate and the false negative rate. Meaning, how often does it say there was gunfire when it was a car backfiring or something else, a glitch in the system? And how often does it fail to detect gunfire?

Chittum: First, our system operates over a wide area. And so you wouldn't think of this as an actual filter, but spatial filtering is the first step in the process. Our system is only triggered when three or more sensors detect a loud impulsive sound. So the sound has to be loud enough to reach three or more sensors spread out over a large area. If somebody slammed a car door, it's not gonna be loud enough to reach three or more sensors. That automatically filters out low-volume impulsive sounds. Then we use some proprietary algorithms to look for things that are characteristic of gunfire. Our system doesn't hear the way you and I hear; it looks at visual representations of sound. So we're looking at waveforms that have a steep sharp peak and a steady decay.

We use a patented mosaic process. And then it goes through a human review process. So for more, well, for more than 13 years now, we have had an incident review center, what we call an IRC, that is staffed by trained human reviewers, and they are reviewing incidents. Now a lot of people mistakenly believe they only use their ears, that they're somehow just listening to an audio recording and trying to determine from that alone whether the sound is gunfire or not gunfire. So we get through all these steps before we publish.

Pesca: Yeah. And so from the statistics I've learned, a false positive, which is when there was an indication of gunfire, when no gunfire occurred, that occurs a third of 1% of the time. And the other side of that coin, missing a gunshot, that happens about a little less than three, maybe 2.5% of the time. Am I getting that about right?

Chittum: That's right.

Pesca: How quickly does it relay this information, by the way?

Chittum: Usually less than 60 seconds. We have a contractual guarantee that we'll publish in less than 60 seconds, 90% of the time. We also guarantee that we will be accurate at least 90% of the time, because our customers depend on the accuracy of the system.

Pesca: And it seems, at least from your statistics and this external audit that you hired, you live up to that, you more than live up to that, you pass that.

Eric Zorn: Tom, when you talk about the system, it does sound almost magical and certainly wonderful. And yet Chicago's mayor wants to cancel it. Officials in Atlanta, Charlotte, New Orleans, San Antonio, and just recently, Houston have said they don’t want to use it anymore. There are clearly municipalities that are not satisfied with the service that ShotSpotter is providing. Can you explain why that would be and what your answer is to the criticisms that those mayors have raised?

Chittum: That's a criticism I hear a lot, but I think it tells only one side of the story. Frequently, people point to the same handful of cities and say, all these cities have not renewed their contract over the course of about 10 years. They never say, well, what about the 170 cities that do have the system, many of which have renewed multiple times, many of which have expanded their coverage?

So this is not a solution for everyone. Cities have a lot of competing demands. I couldn't say with certainty why any of them don't renew. They've got finite dollars. They've got an issue they've got to deal with, but we've never seen anyone say that we don't renew because the system doesn't respect civil rights or it doesn't live up to its technical guarantees. Those are decisions those cities have to make. I intend instead to focus on all of those customers that do think of ShotSpotter as a central component of their comprehensive gun violence reduction strategy.

Zorn: The criticism here in Chicago has been that ShotSpotter results in overpolicing of Black and brown neighborhoods and that it increases friction between the police and residents because police arrive all amped up because they think there's gunfire.

And the other criticism that is raised here quite a lot is that it doesn't really lead to much in the way of crime reduction or prosecutions or even gun confiscations.

Chittum: The criticism that it doesn't lead to lots of arrests overlooks all of the other measures of success. It does, in fact, lead to many arrests. Very often, ShotSpotter is the first event in the chain of events that leads to gun-related arrests. But that's not its only measure, and it's not its most important measure.

Locating the gunshot wound victims that are often left behind at shooting scenes, helping police locate evidence so that they can conduct investigations that lead to downstream investigations. I think those are also important factors too.

And there's another part that is often not discussed in detail, but that's the possibility of using the system to reassure the community. So we hear the criticisms, and somebody said to me recently, “Wow, you have a lot of critics.”

I said, “No, we have loud critics.”

I don't think we have a lot of critics. And in fact, I think the sentiment we've seen from the aldermen in Chicago is that a lot of people want ShotSpotter in their community. They want to see police respond when there's gun violence. But very often, gunfire goes unreported through 911. That chronic underreporting of gunfire has a few different reasons. Some of them are practical. A lot of gunfire happens in the middle of the night, and law-abiding citizens aren’t awake.

They're awakened by something. They don't know what it was, so they don't call. But sometimes, it's heartbreaking. People have resigned themselves to living with it, or they think police don't care. They look out their window, and they don't see police show up. They think police know, but police don't. ShotSpotter helps fill that gap, so police can respond comprehensively. And even if they don't find victims or offenders, low-friction contacts with communities knocking on doors saying, hey, we got a report of gunfire. We're just making sure everyone is OK. Do you see anything? Do you hear anything? If you do call us, we'll show up. I think that can reassure communities that police have not abandoned them.

Zorn: In Chicago, 14 out of the 17 aldermen whose wards are covered by ShotSpotter (and not all of the city is covered by it) have asked the mayor to continue the program in their community. And the Chicago Police Department says that 80% of ShotSpotter alerts in some of the most crime-plagued neighborhoods did not have accompanying 911 calls. And the Chicago Police Department says that first responders have rendered life—saving medical aid 430 times in the last three years, thanks to ShotSpotter.

These are all data points that are animating this conversation. And another thing that's happened here — just for sort of background for listeners — is that, in February, our new mayor, Brandon Johnson, said he was going to get rid of ShotSpotter, but only after the summer, after the Democratic National Convention is here.

He gave no good reason he wanted this extension. The contract expired, and the mayor could have just said, “Well, it's over, we'll go back to the way things used to be.” But he did extend it. Wouldn't it have been possible for Chicago just to turn off the system and go back to status quo before 2018?

Chittum: You'd have to ask the mayor that. But it seems to me that the delay is a tacit admission that ShotSpotter does in fact work, and it's important to have it in place for events like the DNC and through the summer where we see seasonal spikes in violent crime.

Pesca: So if there are critics of ShotSpotter and if they are allowed a technology, a company like ShotSpotter is certainly going to hear it, and you have contracts with municipalities, and informing this is not just, as you heard, the mayor of Chicago criticizing it, there are outside groups, sometimes civil liberty groups including the ACLU that has looked into it. One group is the MacArthur Justice Center. So here are some of their stats, and I'd just like to ask you to respond.

They report, on an average day in Chicago, there are more than 61 ShotSpotter-initiated police deployments that turn up no evidence of any crime, let alone gun crime, and 88.7% of ShotSpotter alerts didn't result in police reporting an incident involving a gun, and there were over 40,000 dead-end deployments over almost two years. They sent the police out, and it was a waste of police time. What about those stats?

Chittum: Well, I think you've got to look at a few different things. First of all, I think it can be misleading to focus on percentages rather than nominal figures. So even if those numbers were right — and they are not — you're still talking about thousands of alerts of gunfire that produce valuable police response, help recover evidence, help locate victims, as Eric pointed out. There are statistics showing that ShotSpotter leads people to gunshot wound victims when no one calls 911. Those are people who would not have gotten aid for that. I also think they overlook some of the practical realities of dealing with crime in an urban area. The physical evidence of shootings is sometimes ephemeral. Casings are small, haphazardly ejected. Witnesses leave the scene; suspects flee. Those studies don't look at things like, well, what was the police response time, and did it have any effect on recovery of evidence?

And it also overlooks the fact that our system audio-records the gunfire, provides an audio recording of it to the police. It is in itself evidence that a shooting has occurred. It's not the sort of evidence that would stand alone by itself in court, but it's still valuable. It's the reason that we see ShotSpotter evidence being used in court every single day all across America, including in Cook County.

Pesca: Eric, I want to ask you about the old idiom, “Look at what I do, not at what I say,” in relation to Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson. So, as we've chronicled, he has been very critical of the technology, saying there's not enough evidence that it works. And yet, when it came time to extend the contract, after making these criticisms, he did extend it for millions of dollars. So is this an example of him using a rhetorical point or a politician making public statements, but not backing it up with action? Or maybe, I don't know, maybe there are some other considerations at play. Mayors have big constituencies; you don't want to get on the wrong side of police. How else to interpret his actual extension of the system that he criticized?

Zorn: It was a very strange moment. He decided that he wanted to end the contract because he had campaigned on that. He's a highly progressive mayor, and he had campaigned on getting rid of ShotSpotter because it is unpopular in many progressive circles.

He could have pulled the plug right away, and he didn't. He extended it through the summer, which suggested to a lot of us who observed the situation that, in his heart, he knows it’s a good crime-fighting tool and he wants it in place for the summer months, which in Chicago are the most violent months — and for the Democratic National Convention in mid-August, which will be a time when the eyes of the country are going to be on Chicago.

He ended up paying ShotSpotter more for this seven-month extension that it had cost the city the entire previous year. Now he has a rebellion on the city council where you have these aldermen who want it in their wards. And the mayor is saying, “Well, no, it’s my right to end the contract.”

But he's put himself into a trick bag. The current superintendent and the three former superintendents have all said to keep it. Most of the aldermen representing the wards where ShotSpotter is in place want to keep it. So the mayor is placing his judgment over the judgment of the people who are most impacted by it. And as an observer of this scene, my inclination is to let the stakeholders make that decision, the people who are affected. I live on the Northwest Side of Chicago. There is no ShotSpotter up here. We don't need it.

Pesca: What's the murder rate in your neighborhood?

Zorn: It's very low. As is gun violence in general. But I am much more interested in what those on the ground, close to the situation, are saying than what me and my neighbors in a comparatively safe community are saying. If the police want it and most community members want it, I am not going to impose my judgment of the statistics on them.

Certainly, there are questions about what metrics we should look at. Does ShotSpotter lead to more prosecutions? Does it lead to more arrests? Does it lead to safer neighborhoods? The answer does seem to be no, not really. But I am not going to say these are the only metrics we should look at.

Pesca: Every month in my field of audio, there are new technologies that do things like take out background noise and recognize what is, say, speech and what is not. AI is getting smarter and smarter. Is that at play with ShotSpotter? Or is your technology, your patents, are they locked in place? Do you predict that there are going to be great improvements in that 97% false negative rate and 0.3% false positive rate?

Chittum: Yeah, so occasionally some of the criticisms that I will hear people make are decades old. ShotSpotter has been around for more than 25 years. And, of course, the system today is not the system of 25 years ago. It is far more effective. Our screening processes have improved. That accuracy rate, you know, when we send an alert out, we don't really know what's on the other end. We really depend on our customers to report back to us. The fact of the matter is that sometimes gunfire will occur and we'll miss it. That's a false negative. Sometimes we'll publish an alert. Customers say that was not gunfire. But to your point, Mike, that was less than 3%. About 97% is the accuracy rate we maintain. And that's across all of our customers and millions of incidents and many years.

Pesca: Eric, in asking that question, am I missing something? Maybe the real tension is not that ShotSpotter can't very reliably say there was a shot fired. It's what happens afterwards, when the humans show up to the scene.

Zorn: That’s certainly the criticism — that police show up to these scenes expecting gunfire so they treat innocent citizens who they run into as potential shooters. And it creates overpolicing in these neighborhoods. Now, the thing is that, when you ask a lot of the people who live in these neighborhoods, they want more policing in their neighborhoods.

Pesca: Well, they want to be sufficiently policed.

Zorn: Some of these groups that are highly critical of ShotSpotter are also ones that are really interested in defunding the police, ending the carceral system and so on. It’s a fairly progressive group of advocates who are fighting against this. But the criticism that they raise is that this money that goes toward ShotSpotter should be going into programs that are more effective at fighting gun violence. So Tom, is this the best use of money, the scarce resources that every city has toward reducing crime and gun violence?

Chittum: Suggesting that you can either have civil rights or ShotSpotter is a false choice. It's not “either/or.” It's “and also.”

I spent an entire career working at the ATF — the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. I'm no stranger to controversial law enforcement issues.

And when I came to this company, I was absolutely shocked by the headwinds that it faces from some critics who would not want police to respond to gunfire.

And what I have concluded is that those loud critics really look at ShotSpotter as a proxy for policing. I think they're opposed to policing generally, and ours is a convenient proxy for it. Because to your very insightful point, the nebulous other long-term solutions, they're not immediate.

And I do think we should be investing in jobs and education, but in the near term, addressing gun violence requires law enforcement. I think policing is an important part of keeping communities safe. And this is just one tool, right? But it's not the hammer that builds the house; the carpenter does.

Police should be using a myriad other tools like cameras, working on improving their relationship with the communities they serve, being transparent about the work they do. It takes a whole lot to make effective public safety.

(post-interview conversation between Pesca and Zorn that aired as a bonus segment)

Pesca: Can you talk more about the idea of deferring to the aldermen who want ShotSpotter in their neighborhood?

Zorn: Sure. The mayor has been saying that it's not possible to have it installed neighborhood by neighborhood. But Chittum disagreed with that.

A poll that ShotSpotter itself conducted showed overwhelming support in these communities. In fact, the lowest level of support for ShotSpotter was 59% in their survey, and that was among white people. People of color show greater levels of support for ShotSpotter. Now, that's of course their own survey that they commissioned. So I don't want to necessarily cite it as a proof-positive. But it does seem to me that when I am sitting here in my relatively safe neighborhood, saying, "You people in these neighborhoods, you don't get to decide whether you want this technology, because I know better." Or "I've looked at these statistics and looked at these metrics. And I say that, that that's what is most important to me as a citizen of the city," that comes off as patronizing and paternalistic.

I feel like the people who are closest to it should be listened to. And that would include the police. I also didn't mention that the police-friendly blogs often promote news showing the positive effects of ShotSpotter. So you've got all of these police superintendents, current and former, who are in favor of it. It just seems to me that those who are most involved with this technology favor it. So who am I to try to cherry-pick various statistics and say no, you can't have this?

And a point you made that I thought was very compelling was that, when you look at the $10 million a year ShotSpotter is costing Chicago, it's a good deal when compared to the lives saved if you put the value of a human life where civil juries tend to place it. Wrongful death suits against the Chicago Police Department and the city often run into the millions.

So if this technology saves a couple of lives a year because first responders get to a gunshot victim faster than they would have, the technology can be thought to pay for itself. I don't have a dog in the fight, as they say. But it's compelling to me that those who have lived experiences with ShotSpotter generally want it.

Pesca: And the municipal budget of your city is $16.6 billion. And so if I do the math, that $10 million expenditure on ShotSpotter comes out to something like a third of 1%. I don't think this is some sort of magical technology, even though that's how Tom put it. But it does seem to me that, if it really didn't work, we wouldn't be hearing complaints just from the advocacy groups complaining that it causes cops to show up where they wouldn't have shown up before. And if you think that is a bad thing, you're probably part of the coalition that elected Brandon Johnson, or else you have a pretty progressive mindset. But to me, the evidence for this is that the cops themselves stand by it, and not just the brass. And when I talked to the police in New York, where we also use the technology, they don't hate it. They say it's a tool. And I know cops well enough to know that they'd grouse about it if it was constantly wasting their time.

Zorn: Clearly there are many instances where it does waste their time. And that's because of the nature of gunfire. When someone shoots another person or blows off a round, they're not going to stand around and wait for the police to show up. They're going to run or drive away. So if police respond to a ShotSpotter alert and can’t find any evidence, is that really a false alarm? I'm not sure how they can say that.

Pesca: The MacArthur Justice Center says it’s a whiff if the alert does not result in police recording any kind of incident involving a gun.

Zorn: It's a complicated technology to study, and when you read the various criticisms and the point-counterpoints online, you find a lot of "What about this? What about that?"

But if failure to prove or solve a crime is the standard, couldn't we say the same thing about 911? Did widespread adoption of hugely expensive 911 emergency systems lower crime rates in big cities?

It’s also relevant to ask if and how the technology is going to improve. I know the ACLU and others complain that this technology "listens in" on neighborhoods because the microphones are always on, and this amounts to an untoward surveillance. But I see stories every day online of crimes that are captured on porch cameras, and streetlight cameras and camera phones. So much crime is now documented that way that to complain about the surveillance of this one technology seems beside the point.

Pesca: I had a friend whose mother was murdered, and 30 years later, they caught the killer because of a DNA database. And I remember the ACLU was against that. I understand the concerns; these things all can be misused. But I suppose if the ACLU was really consistent, I would defer to them and say, "OK, if you're the people who are always going to raise the issue, and then any sort of civil liberty, and you're going to do it consistently, I would say you're doing your job. And you're useful in sort of the way that defense attorneys and prosecutions are useful in an adversarial system."

But that's maybe a conversation for another time. The other point I want to make is that when the New York City Police Department was doing half a million stop-and-frisks a year, they were turning up a lot of guns, they were making a lot of arrests and murder was going down. But there is a trade-off. And society — or at least New York City society — did not want to make that trade-off. There are always trade-offs. And if ShotSpotter is going to make the police show up to an intersection, I think what's really important, and this is a little pie in the sky, is that when the police are there, their interactions have to be what all the chiefs of police say they need to be respectful —and they have to not make people regret the police's presence. I mean, sometimes these communities want more police, but they do so in very ambivalent ways, because they know the presence of police has historically been dangerous and oppressive for them. And the only thing more dangerous is the lack of presence of police.

Zorn: There's tension in stop-and-frisk with constitutional rights. I don't see that with ShotSpotter. It certainly could happen that police could show up and violate people's constitutional rights. But that's possible anytime police show up.

But this debate is playing out here in the context of Mayor Johnson and what he campaigned on. And one of the reasons that Johnson is sticking with it is that he's had to kind of go back on some of his campaign promises, so this is one that he's going to stick to. But he hasn't really made the case to the public for keeping that promise. Plus his current approval ratings are very low, in part because he comes off as very stubborn and dogmatic even though he campaigned on being a collaborative, transparent mayor who was going to work with people.

Now all these alders are saying, "Hey, work with us! We want this!" And Johnson's like, "No, no. I know what's best."

It doesn't make any sense to me that if you're going to end the contract in February, the transition period just happens to last through the summer months. What was it that made it impossible for him just to say, "OL, we're pulling the plug tomorrow”?

Chicago didn't have it before 2018. So the police can just go back to the old way, right? What's with this long transition period? That's kind of a rhetorical question because it's pretty obvious that Johnson realized that there's value in ShotSpotter and the summer in Chicago is historically the worst season for crime. So he's talking out of both sides of his mouth. And this is playing into a larger problem that he has of asserting his authority. For example, he was unable to pass a real estate transfer tax increase to help alleviate homelessness in part because voters didn’t trust his administration to spend the money wisely.

Pesca: Well, as the saying goes, you campaign in poetry and govern in prose. And campaigning in early 2023, he was probably trying to highlight the contrast between him and Paul Vallas, who was the more law-and-order candidate. So he had every incentive to articulate the most progressive ideas. ShotSpotter doesn't work great, right? We've documented that there's no before and after showing that it reduces crime, and some members of the progressive community who speak the loudest are upset with it. So Johnson had every incentive to criticize it. But now it's a little more complicated than rhetoric to rally a progressive coalition.

Zorn: Right. He says things like, "I campaigned on this! People elected me to do this!" But he won with just 52% of the vote, which is a victory — no question — but it wasn't a mandate. And one of the things people liked about him was that he seemed open and he talked a lot about collaborating and being this open new kind of mayor rather than the more authoritarian style that he saw with Daleys and Rahm Emanuel. But now he's “my way or the highway” on ShotSpotter, which does not seem to be in tune with public opinion. He's really dug in his heels. It just seems like a fight that he wouldn't want to pick right now because he's had so many losses.

Note: I have written to StopShotSpotter and hope to publish a response from that organization here next week.

Land of Linkin’

New York Post: “Ingrid Andress’ music is taking off after drunk national anthem debacle.”

Snopes reports that a weird internet meme about JD Vance is totally false.

Meathead’s Amazing Ribs: “Beer Can Chicken Recipe: There Are Better Ways To Cook Chicken.” He writes, “Beer Can Chicken remains a gimmick, an inferior cooking technique, a waste of good beer, and it is potentially hazardous. … Think about this: You’ve never seen a fine dining restaurant serve Beer Can Chicken, have you? That’s because professional chefs know this is clearly not the best way to roast a chicken.”

Squaring up the news

This is a bonus supplement to the Land of Linkin’ from veteran radio, internet and newspaper journalist Charlie Meyerson. Each week, he offers a selection of intriguing links from his daily email news briefing Chicago Public Square:

■ Off Message columnist Brian Beutler on Republican smears against Harris: “Some of them are harmless … but eventually one will snowball into a big problem.”

■ Donald Trump niece Mary L. Trump: “Donald is terrified.”

■ Columnist Julia Gray: “I love watching the powerful White men of this country s**t themselves.”

■ Veteran Chicago newspaper editor-turned-media-critic Mark Jacob: “Harris is breaking Republican brains.”

■ Columnist Jeff Tiedrich: “Chill the f**k out, we’ve got this.”

■ Wired says Trump’s running mate, JD Vance, left his Venmo account public—exposing his “close ties to the very elites he rails against.”

■ Sun-Times Editorial Board member Rummana Hussain—herself in an interracial marriage—wonders what Vance’s wife sees in a party “crawling with bigots triggered by her Brown skin.”

■ KamaLexicon: Some memetic concepts to add to your vocabulary as the presidential campaign unfolds—including coconut-pilled, brat, KHive and childless cat lady.

■ Satirist Andy Borowitz: “Nation’s Cats Lash Out at J.D. Vance.”

■ Cartoonist—and award-winning former Tribune photographer—Alex Garcia files a strip mocking cable pundits’ love of the word look.

■ “Lightningwriter” columnist Charlie Madigan on election speculation: “I read this awful story from the Washington Post … so you don’t have to!”

■ Moline-based John Deere management: Sorry about embracing that Pride stuff and pronoun policies.

■ Block Club: The intro to Bob Newhart’s eponymic TV series set in Chicago made no geographic sense.

You can (and should) subscribe to Chicago Public Square free here.

Mary Schmich: Eight words on the recent political news

My former colleague Mary Schmich posts occasional column-like entries on Facebook. Here, reprinted with permission, is a recent offering:

On Sunday, an hour after Joe Biden announced he wasn't running, I posted 5 words:

Hard. Brave. Sad. Right. Scary.

Two days later, I'd add 3 more:

Exciting. Energizing. Hopeful.

Minced Words

Of all the weeks for me to be on vacation! The panel discussion was lively without me as host John Williams, Austin Berg, Cate Plys and Marj Halperin discussed the Democratic presidential swap out and the ghastly police shooting of Sonya Massey by Sangamon County Sheriff’s Deputy Sean Grayson. Subscribe to the Rascals wherever you get your podcasts. Or bookmark this page. If you’re not a podcast listener, you can hear an edited version of the show at 8 p.m. most Saturday evenings on WGN-AM 720.

Read the background bios of some regular panelists here.

Quotables

A collection of compelling, sometimes appalling passages I’ve encountered lately

I don't expect much of the national media, but please, can they just be very clear and up front about the fact that "DEI" is the right's substitute for the n-word? It's very obvious, there's no point in pretending there's any ambiguity or doubt, just treat it like the fact it is. — David Roberts

Republicans criticize Kamala Harris for laughing and smiling. Maybe they don’t understand that people like to laugh and smile. Maybe they don’t know those are normal things that well-adjusted human beings do. — Mark Jacob

I clicked “White Noise” on my sleep app last night and it played a JD Vance speech. — Steve Marmel

Kamala, I call her laughing Kamala. Do you ever watch her laugh? She’s crazy. You know, you can tell a lot by a laugh. No, she’s crazy. She’s nuts. — Donald Trump

If you think the attacks on Kamala for not having any children are misogynistic, imagine if she had 5 kids by 3 different men. — @OhNoSheTwitnt

(President Joe Biden) must resign and the 25th Amendment must be used to remove him from the presidency. So it was written in the Constitution, by patriots who pledged their lives and sacred honor and gave us this republic. — John Kass, seemingly unaware that the 25th Amendment was adopted in February 1967 and would not need to be invoked if the president resigned

Quips

In Tuesday’s paid-subscriber editions, I present my favorite quips that rely on visual humor. Subscribers vote for their favorite, and I post the winner here every Thursday:

The new nominees for Quip of the Week

Since I’m traveling I’m subjecting readers to another in a series of dad jokes from social media — mostly excruciating puns. I tender my apologies in advance.

As always, I don’t attribute these jokes to any one source, since I find that dad jokes are the most frequently stolen or misattributed jokes on the internet.

What are a comedian's pronouns? He/he/he.

I finished last in an origami contest because I refused to fold under pressure.

Doctor: I’m diagnosing you with onomatopoeia Me: What’s that? Doctor: Exactly what it sounds like.

If you want a nice quiet lunch, try a Shhhushi Bar.

What smells better than it tastes? A nose.

I’ve asked tons of people what LGBTQIA+ stands for and no one’s given me a straight answer.

Horses originated on the Gallopitgoes Islands.

I'm thinking about investing in stocks. Chiefly chicken and vegetable. I'm hoping to be a bouillonaire.

What do you call it when one banana eats another? Cannibananabalism.

I know it's a long shot but does anyone know what a trebuchet is?

Vote here and check the current results in the poll.

For instructions and guidelines regarding the poll, click here.

Good Sports

The No-No Sox

As long as the race remains close I will offer you comparison standings of the 2024 White Sox with the 2003 Detroit Tigers and the 1962 New York Mets, teams that have defined futility for more than 80 years, and the 1916 Philadelphia Athletics, the worst team in baseball’s modern era (20th century on).

After 104 games:

The 1916 Philadelphia A’s played a 153-game season and finished 36-117. Out to another decimal place, that’s a winning percentage of .2353. The Sox play in a 162-game era. If they go 38-124, that will be a winning percentage of .2346. So the magic number of victories in the remaining 58 games needed for the Sox to end up with a better winning percentage than the 1916 A’s is now 12 if they lose.

If and when the Sox have at least a three-game lead over this ignominious field, I’ll discontinue this weekly feature.

Tune of the Week

No tune this weekI’ve been opening up Tune of the Week nominations in an effort to bring some newer sounds to the mix. I’m asking readers to use the comments area for paid subscribers or to email me to leave nominations (post-2000 releases, please!) along with YouTube links and at least a few sentences explaining why the nominated song is meaningful or delightful to you.

The Picayune Sentinel is a reader-supported publication. Browse and search back issues here. Simply subscribe to receive new posts each Thursday. To support my work, receive bonus issues on Tuesdays and join the zesty commenting community, become a paid subscriber. Thanks for reading

Contact

You can email me here:

I read all the messages that come in, but I do most of my interacting with readers in the comments section beneath each issue.

Some of those letters I reprint and respond to in the Z-mail section of Tuesday’s Picayune Plus, which is delivered to paid subscribers and available to all readers later Tuesday. Check there for responses.

If you don’t want me to use the full name on your email or your comments, let me know how you’d like to be identified.

If you’re having troubles with Substack — delivery, billing and so forth — I’m happy to help.

Boy, Kass has really gone over the edge, hasn't he?

I'm going to say something out loud that is going to upset some people. There is a lot more crime in black and brown communities than white communities. There, I said it. I'm not supposed to say it because I am white and that automatically makes me racist. Besudes, I supposedly can't understand what is happening in these communities. But I have spent my entire adult life wondering how we can solve problems we cannot accurately state. Note I did not attempt to state a reason or judge anyone. I merely stated a fact. Shot Spotter was not designed to solve crimes. It doesn't care about the ethnicity of the criminals or vvictims. It merely identifies sound. Will it hear sound more often in black and brown communities? Yes, if there are more shootings in those areas. Note that Shot Spotter accuses or arrests no one. The police do that if they catch anyone. Criticism of Shot Spotter ignores that once police get to a shooting scene, either the perps still need to be there or they need the cooperation of witnesses unless there has been other evidence left at the scene. These, to me, are the real issue, not Shot Spotter. Shot Spotter does not identify shooters, so how can it be unfairly targeting black and brown people, unless guns used by black and brown shooters somehow sound different? So the only real argument against it should be whether or not the cost is worth it in catching felons. The issue of Brandon Johnson has been addressed by me many times. He may be the greatest mayor in the history of Chicago at using a lot of words while saying nothing. He is like a dog with his nose constantly in the air testing the scents. Is he for or against something? That depends on what the black community leaders and the CTU are telling him. I'll give him credit for remembering who got him elected. But it's not a great leadership quality.